Syngenta just drew on its past to prepare for the future.

Formed in 2000 when drugmakers Novartis and AstraZeneca merged their crop care businesses, the seed-and-pesticide maker just announced a big step up in its R&D capabilities in biological solutions thanks to a deal with one of its pharma founders.

Syngenta has acquired natural compounds and genetic strains from Novartis to explore new leads in agriculture, while Novartis retains exclusive rights to the repository for pharmaceutical use.

“There is a bit of a misconception between what we do in Ag and pharma,” Camilla Corsi, Syngenta’s global head of crop protection R&D.

“The reality is that, today, agriculture utilizes the same sophisticated technology. Pharma is usually at the forefront and driving a greater level of investment. In Ag, we can fully leverage some of this investment because we are not competing with each other.”

The transaction includes Novartis’s Natural Products & Biomolecular Chemistry team and a lease on a fermentation pilot plant and laboratories in Basel, Switzerland, where the now Chinese-owned Syngenta is still based. Corsi said the additional fermentation capacity is coming at the right time given her growing pipeline of leads that will need pilot runs.

“We know the asset and the team so there’s almost no transition,” Corsi said in an interview with chemicalESG. “When you build something, it can take 2-3 years; it’s a very different timescale.”

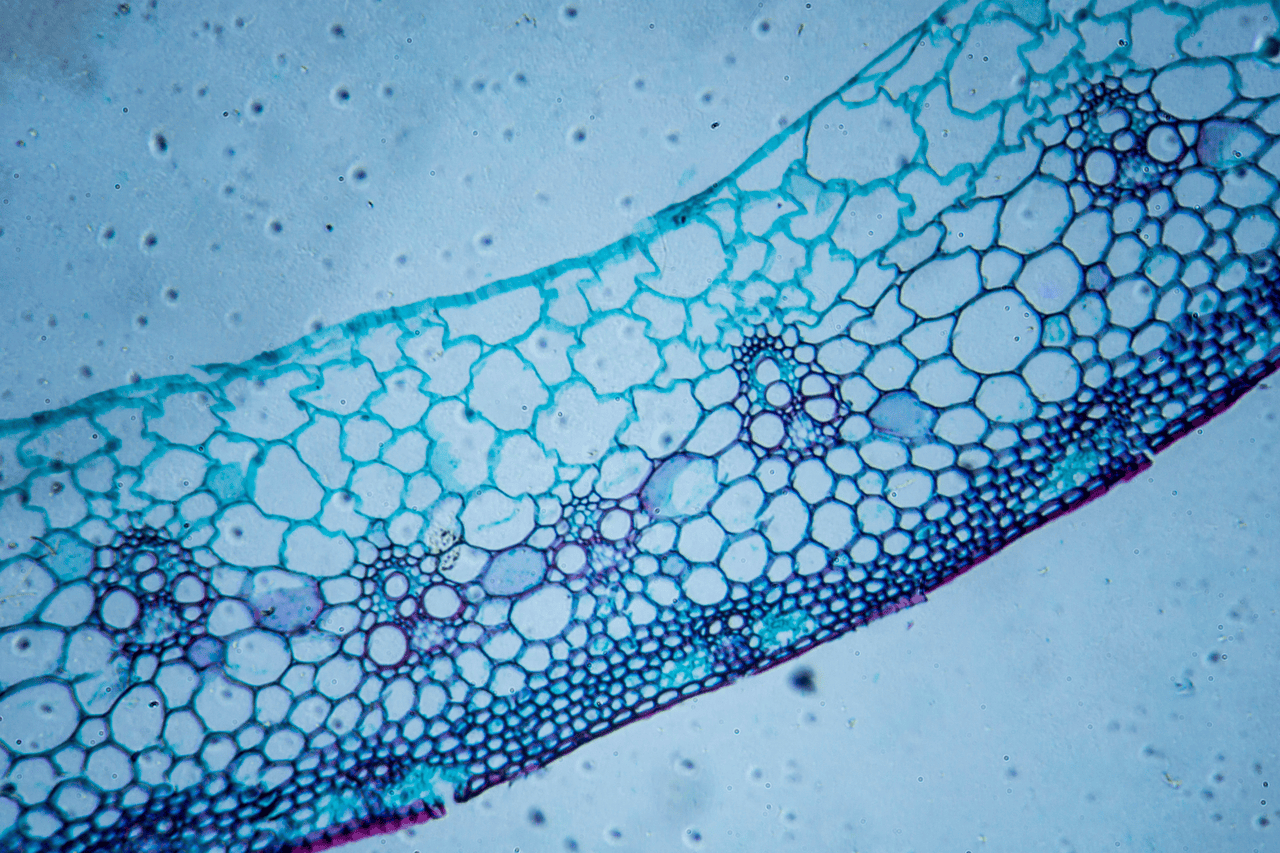

Novartis had been working on metabolites from microorganisms and plants that could be used in anything from cancer drugs to infection control. Syngenta will turn this huge library of natural compounds and strains toward weeds, fungi, and insects.

The hunt for a replacement for synthetic chemistry like glyphosate, the world’s most widely used herbicide, is through biocontrol products.

Unlike traditional chemical-based solutions, biocontrol products can be given a more specific spectrum of efficacy, while decomposing into natural components.

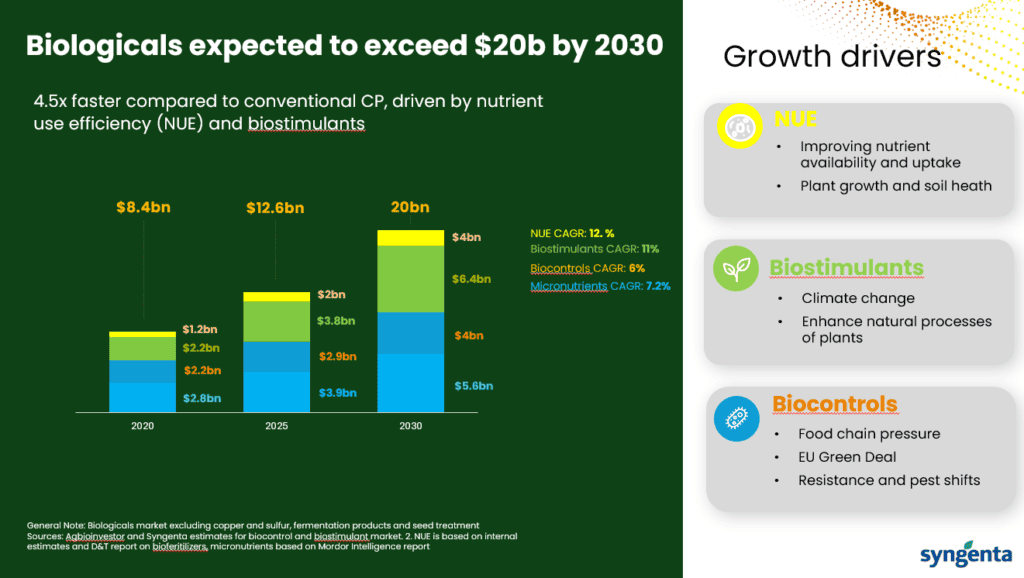

The industry is heavily investing in biostimulants that bolster plant strength to help them withstand drought and other stresses, and in nutrient use efficiency for natural processes like nitrogen fixation and phosphorus solubilization.

Syngenta and Novartis have been collaborating since 2019. But now, more than ever, the overlap between pharma and Ag is leading to greater collaboration in bioengineering, data science, fermentation, downstream processing as well as analytics. Most of Syngenta’s previous tie-ups have been with crop-focused biotech firms although in 2021 it did enter into a collaboration with Insilico Medicine to harness AI and deep learning.

Bayer is somewhat uniquely positioned here, having both pharma and crop-care under the same roof, at least for now. The Monsanto-glyphosate-litigation aside, when it comes to biologics, the intersection is working well with a lot of collaboration between respective R&D teams, especially in precision molecules.

“It turns out it’s basically the same exercise,” Bayer CEO Bill Anderson said. “With the crystal structure of the protein of a target, you can use that in designing a molecule instead of just throwing molecules against the wall and seeing what sticks. We’re doing that to a great degree in pharma, and in Crop Science.”

Both Bayer’s CropKey and its drug discovery platform Vividion are applying the same kind of learnings to target “really tricky proteins,” he added.

The opportunity is becoming increasingly apparent. The share of biologics in the crop-protection market is expected to double to about 20% by 2030. The race is on to improve the efficacy and reliability across different seasons and crops, while lowering the cost, which has hindered the uptake so far, especially in row crops, Syngenta’s Corsi said in the interview.

“We are starting to see technology where we will have biological efficacy similar to the chemical ones. This is the kind of breakthrough technology that the market is waiting for,” she added. “Are we at the inflection point, probably not yet in full.”

And there’s a whiff of change in the air in terms of Europe’s regulatory approach to the technology. As part of its Vision for Agriculture and Food, the European Commission suggested improving aspects of the current regulation to help accelerate the access of biological crop protection products in the EU.

Farmers and industry are hoping for a more fundamental change, with the separation of biologics from the framework controlling chemical pesticides. That isn’t a reality yet, but Corsi is optimistic.

“We’ve been waiting for this for years,” Corsi said. “Now it’s being discussed as an opportunity, which gives us confidence. We believe that there will be a utilization of both chemical and biological technologies in combination. There are some markets that will just require biological, but across the world and multiple crop segments, there will be an integration.”